Francis Tyers

Development and debugging

Lexicon construction

So, you’ve got your morphotactics more or less sorted out, and you’ve made a good start on your morphophonological rules. Where are you going to get the lexemes ? Depending on the language you choose you may already have a beautifully prepared list of stems. For other languages there might be a dictionary with less elaborate systems of classes, perhaps traditional ones that underspecify the morphology, or perhaps ones that don’t specify the morphology at all. In the worst case you may have to just rely on a Swadesh list or a simple list of inflected forms from a corpus.

In any case, whether you have a complete system or just a list of inflected forms, the best idea is to work adding words to the lexicon by frequency of appearance in whichever corpus you have. You might have easy access to a corpus, if not you can use a Wikipedia database backup dump or you can write a webcrawler for some online newspaper. You can use WikiExtractor.py script to extract raw text from Wiki dump.

- Download the latest version of Guaraní Wikipedia.

- Go to Wikipedia database backup dumps

- Find the link for

gnwikiand click on it. - Download the file that ends in

-pages-articles.xml.bz2.

- Run

WikiExtractor.pyusing the following command:

$ python3 WikiExtractor.py --infn gnwiki-20191120-pages-articles.xml.bz2

You will get a lot of output representing the names of the articles in the Wikipedia.

TIP: If you get an error like No such file or directory, try doing ls *.bz2 to find the name of the file.

Now you have wiki.txt file, this contains all the text from Wikipedia.

We can get a frequency list using simple bash script:

$ cat wiki.txt | tr ' ' '\n' | sort | uniq -c | sort -nr > hitparade.txt

This takes the text in wiki.txt, applies a transforms all spaces into newlines \n, then it sorts

the list and counts -c unique instances. These are then sorted again by number of instances.

You can look at the first 10 lines of output like this:

$ head hitparade.txt

19665 ha

6694

4350 peteĩ

4299 de

3581 umi

3331 haʼe

3066 avei

2926 ary

2293 pe

2174 upe

We can find out the number of words in the frequency list:

$ wc -l hitparade.txt

101089 hitparade.txt

Let’s compare this output with part of speech and gloss in English.

| Num | Grn | POS | Eng |

|---|---|---|---|

| 19665 | ha | CCONJ | “and” |

| 4350 | peteĩ | DET | “a” |

| 4299 | de | PREP | “of” |

| 3581 | umi | PRON | “this” |

| 3331 | haʼe | VERB | “be” |

| 3066 | avei | ADV | “also” |

| 2926 | ary | NOUN | “day” |

| 2293 | pe | LOC | “in” |

| 2174 | upe | PRON | “that” |

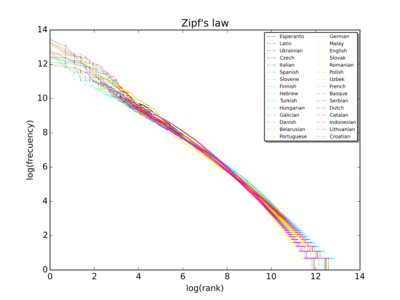

The picture below shows a graphical representation of Zipf’s law.

As you can see the most frequent words are unsurprising for a text from Wikipedia, words about time and place, closed category words like conjunctions, adpositions and pronouns and copula verbs. This was from a corpus of around 431,826 tokens, so the list won’t be so representative for the language as a whole, but the bigger and more balanced the corpus the more legit the frequency list is going to be and the better it is going to represent the language that your analyser is likely to be asked to process.

More on morphotactics

When moving from making a morphological model of a few words from a grammar to making one that covers a whole corpus you are bound to come across some examples of things that are either underdescribed or not described at all in the extant grammars. For example, how loan words are treated and how to deal with numerals or abbreviations which take affixes according to how the words are pronounced and not how they are written.

Loan words

Guaraní local nasalisation rules do not work for Spanish loans. Thus, we have irũme but asociaciónpe, the form of the locative does not change despite following a nasal. How to deal with that? Introduce some archiphoneme that will “cancel” the nasalisation rule.

For example we can introduce a new lexicon N-SPA and an archiphoneme %{s%}, see code below:

LEXICON N-SPA

:%{s%} N ;

LEXICON Nouns

irũ:irũ N ; ! "amigo"

asociación:asociación N-SPA ;

declaración:declaración N-SPA ;

¡OJO! Don’t forget to add %{s%} to the set of Multichar_Symbols.

Now we can add an exception to nasalisation rule we defined earlier in twol file. This way the transducer will overlook the cases where the nasalisation is not needed.

You should first add the pair %{s%}:0 to the alphabet, as %{s%} will never surface as anything aside from 0.

"Surface [m] in loc affix after nasals"

%{m%}:m <=> Nas: %>: _ ;

except

%{s%}: %>: _ ;

Then recompile and try running

$ hfst-fst2strings grn.gen.hfst | grep loc

apyka<n><loc>:apykape

asociación<n><loc>:asociaciónpe

ava<n><n><loc>:avape

declaración<n><loc>:declaraciónpe

irũ<n><loc>:irũme

tembiasa<n><loc>:tembiasape

óga<n><loc>:ógape

Numerals and abbreviations

Numerals and abbreviations also present a problem: they do not provide us with any information at all about how the word should be pronounced (as they are written in digits or letter symbols). Take a look at this following example:

| Onohẽ | iPod | ary | 2001-me | ha | ary | 2003-pe | tienda online | vendeha | puraheikuéra | ha iTunes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SG3-release | iPod | year | 2001-LOC | and | year | 2003-LOC | shop online | sell-SUBST | song-PL | and iTunes |

- “They released the iPod in 2001 and in 2003 started to sell songs in an online shop and on iTunes”.

The ajacent suffix depends on the pronounciation of the final digit in the number, for example, 1 is pronounced as peteĩ where the final ĩ is nasal and 3 is pronounced as mbohapy where y is not nasal.

Thus we can have a lexicon of digits with the archiphoneme, for example, %{d%} indicating whether the nasal alternation should be done or not.

Here is an excerpt from a transducer in lexc that handles numeral expressions:

LEXICON NUM-DIGIT

%<num%>:%- CASE ;

LEXICON LOOP

LAST-DIGIT ;

DIGITLEX ;

LEXICON LAST-DIGIT

1:1%{d%} NUM-DIGIT ; !"peteĩ"

3:3 NUM-DIGIT ; !"mbohapy"

LEXICON DIGITLEX

%0:%0 LOOP ;

1:1 LOOP ;

2:2 LOOP ;

3:3 LOOP ;

4:4 LOOP ;

5:5 LOOP ;

6:6 LOOP ;

7:7 LOOP ;

8:8 LOOP ;

9:9 LOOP ;

It is not complete but it should give you enough pointers to be able to implement it.

You can add the rest of the Guaraní numerals to the lexicon:

- 0 - papaʼỹ

- 2 - mokõi

- 4 - irundy

- 5 - po

- 6 - poteĩ

- 7 - pokõi

- 8 - poapy

- 9 - porundy

Note that in the Alphabet in your twol file you can specify these kind of symbols as always going to 0:

Alphabet

A B Ã C D E Ẽ G G̃ H I Ĩ J K L M N Ñ O Õ P R S T U Ũ V W X Y Z Ỹ Á É Í Ó Ú Ý F Q

a b ã c d e ẽ g g̃ h i ĩ j k l m n ñ o õ p r s t u ũ v w x y z ỹ á é í ó ú ý ʼ f q

%{m%}:p

%{m%}:m

%{s%}:0

%{d%}:0

This saves you writing rules to make them correspond with nothing on the surface.

Try to implement a rule that takes into account this alternation.

When you have finished you should be able to analyse:

$ echo "2001<num><loc>" | hfst-lookup -q grn.gen.hfst

2001-me

$ echo "2003<num><loc>" | hfst-lookup -q grn.gen.hfst

2003-pe

Evaluation

As with all tasks, there are various ways to evaluate morphological transducers. Two of the most popular are naïve coverage and precision and recall.

Coverage

The typical way to evaluate coverage as you are developing the transducer is by calculating

the naïve coverage. That is we calculate the percentage of tokens in our corpus

that receive at least one analysis from our morphological analyser. We can do this easily

in bash, for example:

$ total=`cat wiki.txt | sed 's/[^a-zA-Z]\+/ /g' | tr ' ' '\n' | grep -v '^$' | wc -l`

$ unknown=`cat wiki.txt | sed 's/[^a-zA-Z]\+/ /g' | tr ' ' '\n' | grep -v '^$' | hfst-lookup -qp grn.mor.hfst | grep 'inf' | wc -l`

$ echo "(($total-$unknown)/$total)*100" | bc -l

.26811417711107473200

So our current Guaraní analyser has a coverage of 0.26%… not very impressive yet!

Note: If your coverage is different from the number you see here, do not worry, so long as it is around the same (to within 5%) it’s probably just an effect of having different versions of the same corpus.

Alternatively it would be possible to write a Python script. A good rule of thumb is that given an an average sized corpus (under one million tokens) for averagely inflected language (from English to Finnish) 500 of the most frequent stems should get you around 50% coverage, 1,000 should get you around 70% coverage, and 10,000 should get you around 80% coverage. Getting 90% coverage will mean adding around 20,000 stems.

You can take the bash code from above and put it in a file called coverage.sh, this will allow you to calculate the coverage

easily as you continue improving the transducer.

$ bash coverage.sh

.26811417711107473200

Precision and recall

The second way is to calculate precision, recall and F-measure like with other NLP tasks. To calculate this you need a gold standard, that is a collection of words annotated by a linguist and native speaker which contain all and only the valid analyses of the word. Given the gold standard, we can calculate the precision and recall as follows:

- Precision, P = number of analyses which were found in both the output from the morphological analyser and the gold standard, divided by the tot al number of analyses output by the morphological analyser

- Recall, R = number of analyses found in both the output from the morphological analyser and the gold standard, divided by the number of analyse s found in the morphological analyser plus the number of analyses found in the gold standard but not in the morphological analyser.

Thus, suppose we had the following:

There is a script evaluate-morph that will calculate precision, recall and F-score for output from an analyser for a set of surface forms.

As these kind of collections are hard to come by — they require careful hand annotation — some people resort to producing a pseudo-gold standard using an annotated corpus. However, note that this may not contain all of the possible analyses so may misjudge the quality of the analyser by penalising or not giving credit to analyses which are possible but not found in the corpus.

In all cases a random sample of surface forms should be used to ensure coverage of cases from across the frequency range.

Generating paradigms

A finite-state transducer can be used in addition to produce either paradigm tables or all the forms

of a given word. First we produce a transducer which accepts the stem we are interested in plus

the lexical category and any number of other tags, ?*:

$ echo "i r ũ %<n%> ?*" | hfst-regexp2fst -o irũ.hfst

Then we compose intersect the whole morphological generator with this transducer to find only those paths which start with that prefix:

$ hfst-compose-intersect -2 grn.gen.hfst -1 irũ.hfst | hfst-fst2strings

This is less useful than it may appear because it also produces all of the derived forms. If we want to just include the inflected forms we can just list the forms we want to generate for a given part of speech in a file, for example:

$ cat noun-paradigm.txt

%<n%> %<nom%>

%<n%> %<gen%>

%<n%> %<ins%>

%<n%> %<pl%> %<gen%>

%<n%> %<pl%> %<nom%>

%<n%> %<pl%> %<ins%>

Then compile this file into a transducer in the same way:

$ cat noun-paradigm.txt | sed "s/^/i r ũ /g" | hfst-regexp2fst -j > irũ.hfst

Then finally compose and intersect with our transducer:

$ hfst-compose-intersect -2 grn.gen.hfst -1 irũ.hfst | hfst-fst2strings

This kind of full-form paradigm is useful for debugging, and also for generating training data for fancy machine-learningy type things. It can also help with low-resource dependency parsing (systems like UDpipe allow the use of external dictionaries at training time).

Segmenters

An additional benefit of working with these kind of transducers is that they can be used to make

systems for surface form segmentation. For example given the input ogakuérape produce the

output oga>kuéra>pe.

These kind of segmenters can be useful in various downstream tasks, such as machine translation and other language modelling tasks where reducing the size of the vocabulary (total number of wordforms) can be important.

We will need to do two things, the first is set up our phonological rules file to produce surface forms with the morpheme boundaries still specified. The second is create a new phonological rules file to remove the morpheme boundaries from the analyser and generator.

First let’s remove the rule that removes the morpheme boundary in the file grn.twol and recompile

by typing make.

$ hfst-fst2strings grn.gen.hfst | grep loc

akãvai<n><loc>:akãvaí>pe

apyka<n><loc>:apyká>pe

asociación<n><loc>:asociación>pe

ava<n><n><loc>:avá>pe

declaración<n><loc>:declaración>pe

irũ<n><loc>:irũ>me

óga<n><loc>:ógá>pe

tembiasa<n><loc>:tembiasá>pe

Now we have a transducer that maps from analyses, e.g. akãvai<n><loc> to surface forms with morpheme

boundaries in akãvaí>pe.

We now need to make a new .twol file, let’s call it grn.mor.twol that removes morpheme boundaries:

Alphabet

A B Ã C D E Ẽ G G̃ H I Ĩ J K L M N Ñ O Õ P R S T U Ũ V W X Y Z Ỹ Á É Í Ó Ú Ý F Q

a b ã c d e ẽ g g̃ h i ĩ j k l m n ñ o õ p r s t u ũ v w x y z ỹ á é í ó ú ý ʼ f q

%> ;

Rules

"Remove morpheme boundary"

%>:0 <=> _ ;

Compile the file using,

$ hfst-twolc grn.mor.twol -o grn.mor.twol.hfst

Reading input from grn.mor.twol.

Writing output to grn.mor.twol.hfst.

Reading alphabet.

Reading rules and compiling their contexts and centers.

Compiling rules.

Storing rules.

And then apply it to the generator, grn.gen.hfst using the following command:

$ hfst-compose-intersect -1 grn.gen.hfst -2 grn.mor.twol.hfst -o grn.mor.hfst

Check that the file contains the right strings:

$ hfst-fst2strings grn.mor.hfst | grep loc

akãvai<n><loc>:akãvaípe

apyka<n><loc>:apykápe

asociación<n><loc>:asociaciónpe

ava<n><n><loc>:avápe

declaración<n><loc>:declaraciónpe

irũ<n><loc>:irũme

tembiasa<n><loc>:tembiasápe

óga<n><loc>:ogápe

Looks good!

So now we have two transducers:

grn.gen.hfst |

grn.mor.hfst |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Left | Right | Left | Right |

akãvai<n><loc> |

akãvaí>pe |

akãvai<n><loc> |

akãvaípe |

In order to make a segmenter, we should invert the transducer grn.mor.hfst to get the analysis on the right side and

then compose it with the grn.gen.hfst transducer. Try the following command:

$ hfst-invert grn.mor.hfst | hfst-compose -1 - -2 grn.gen.hfst -o grn.seg.hfst

And then you can try using it:

$ echo "akãvaípe" | hfst-lookup -qp grn.seg.hfst

akãvaípe akãvaí>pe 0,000000